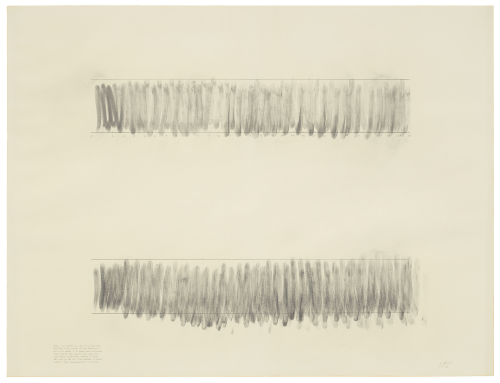

Robert Morris, Blind Time (XXXVIII), 1973

Graphite on paper

35 x 46 inches; 88.9 x 116.8 cm

For today's blog, we invited Pepe Karmel to write about Robert Morris' Blind Time drawings. Pepe Karmel is an Associate Professor of Art History at New York University.

With their visible traces of moving hands and fingers, Robert Morris’ Blind Time drawings ought to belong to the tradition of gestural abstraction. But the uneven marks, repeated in rows or gathered in clumps, have none of the brio associated with abstract expressionism. Conversely, their wavering repetitions lack the soothing regularity of minimalism.

There is a minimal, algorithmic logic to Blind Time (XXXVIII), from 1973. As the neatly lettered inscription at lower left explains:

Working in the measured area above the left hand makes 5-inch high counting strokes of 2 per second for a total of 60 strokes in 30 inches within a 30 second timed interval. Then with the eyes closed the right hand, working below, attempts to repeat the work of the left in an estimated 30 second interval. Time estimation error: +2 seconds.

At first glance, the definition of a procedure that will generate the work of art recalls the work of contemporaries like Sol LeWitt, whose Wall Drawing #146, 1972 (Guggenheim Museum, Panza Collection) has no permanent existence but can be recreated by following the artist’s instructions to draw “All two-part combinations of blue arcs from corners and side and blue straight, not straight and broken lines.”

However, the results of the two sets of instructions are radically different. LeWitt’s directions generate a room-sized mural: a crisp, elegant grid evolving from curves to angles as it unfolds from left to right. Morris’ directions yield a drawing at the scale of the human body, with graphite smudges battering against the clean pencil lines meant to contain them. The fact that the artist makes his first set of marks with his eyes open and the second set with his eyes shut suggests that the first will be clean and regular, the second messy and irregular.

But disorder sets in immediately. Already in the top half of Blind Time (XXXVIII), Morris stacks the deck against himself by working with his left hand, applying the graphite with his fingertips. From the outset, the smeared graphite strokes fail to remain within their intended boundaries, occasionally veering above the upper line and frequently descending below the lower.

The instructions prescribe a rhythm of two strokes per second, continued for thirty seconds, over a span of thirty inches. Logically, then, there should be two graphite strokes within each one-inch segment. (The inches are neatly marked off along the lower border of the band.) In practice, it proves impossible to maintain this regular syncopation. Morris starts too far to the right, so that the first inch contains only one stroke. The following strokes come fast and furious, tilting to left and right, so that it is impossible to say how many strokes are found within any given inch. The dark initial smears fade to a ghostly silver, but he compensates by pressing harder at the end of each downward stroke.

In the lower half of the drawing, Morris repeats the exercise with his eyes closed but using his right hand. The strokes are applied with more consistent pressure, and they seem to be spaced more evenly, although more of them descend below the lower boundary. Trying to maintain the same rhythm and the same rightward motion, he completes the task in thirty-two seconds rather than thirty, and the last two strokes fall outside the guidelines. Still, it is a remarkable performance. Morris’ fingers move across the page like blindfolded dancers, letting kinesthetic sensation regulate movement without vision to guide it.

As Morris wrote in his 1966 “Notes on Sculpture,” his Minimal sculptures were intended to heighten viewers’ phenomenological awareness of “existing in the same space as the work.” They “[took] relationships out of the work and [made] them a function of space, light, and the viewer’s field of vision.” The Blind Time drawings similarly insist on the primacy of the phenomenological over the conceptual but require viewers to step out of themselves and assume the place of the artist, as if their own hands and limbs are creating the marks on the sheet before them.

In later iterations of the series, Morris expands the idea of phenomenological imagery to include historical as well as individual experience. For instance, in Blind Time (Grief) VI, from 2009, he responds to the endless “war on terror” by asking viewers to see the different zones of his drawing as corresponding to different social groups:

(1) At top, “the profiting overclass,” represented by graphite marks made by hands clutching a hundred-dollar bill;

(2) In the middle, “the underclass who absorb the wounds,” represented by slashes of burnt sienna;

(3) At bottom, “the dead,” represented by mars black applied with pounding fists.

The drawing reminds us that grief, like knowledge, is a bodily sensation.

-Pepe Karmel