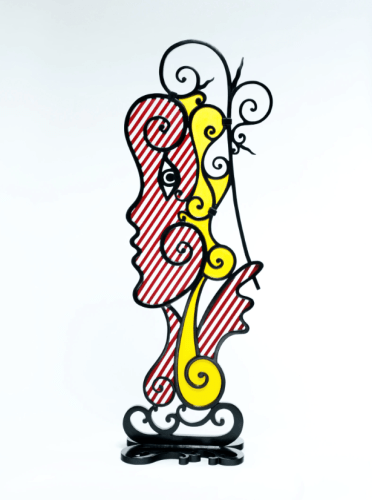

Roy Lichtenstein, Surrealist Head II, 1988

Painted and patinated bronze; 35 1/8 x 14 ¼ x 5 7/8 inches (89.2 x 36.2 x 14.9 cm)

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein, Profile Head, 1988

Painted and patinated bronze; 36 5/8 x 22 ½ x 9 ½ inches (93 x 57.2 x 24.1 cm)

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Does the hair make the woman? Two of Roy Lichtenstein’s bronze sculptures, Profile Head and Surrealist Head II, are two-dimensional drawings in space of women’s faces in profile. Nearly identical in size and format—both are three-foot-high representations from the neck up—the primary facial features of forehead, nose, lips, and chin, however elegantly described with black paint, function as pretexts for the articulation of the highly theatrical hairdos, painted bright yellow.

Profile Head, face turned upwards, is adorned from top to bottom with a twisting column of hair. Thick swaths luxuriously spill down, feathered like Farah Fawcett’s famous coif, also resembling Lichtenstein’s signature brushstroke imagery. Lichtenstein had been using the visual shorthand for some time, recently completing a rather grotesque series of bronze Brushstroke Heads, and continued to rephrase its potential as metonym for painting.

Roy Lichtenstein, Brushstroke Head II, 1987

Painted and patinated bronze; 28 7/8 x 13 ¼ x 17 ¼ inches

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Lichtenstein styled the tresses of Surrealist Head II far differently. The column of hair appears as a stack of spirals complementing the chin and forehead which are also rendered with decorative scrolls, offsetting the jagged linearity of the facial features. The title of the sculpture suggests that it further elaborates the disassembled post-Cubist face that Lichtenstein previously explored in his 1986 sculpture Surrealist Head. The second iteration is more constrained and refined, closer to Deco than Dali, evoking the structured hairstyles of 1920s Surrealist muses like Kiki de Montparnasse.

We are considering these two as a pair not only because of their chronological, media, and formal similarities, but because their geneses were conjoined in Lichtenstein’s creative process. Initial sketches in graphite show the two heads facing each other across a single sheet of paper. Lichtenstein’s more resolved study in tape, painted paper, and graphite on Bainbridge board also positions the two sculptures tête-à-tête. Are these works two sides of the same coin, or perhaps representatives of the enduring art-historical dualism of the classical and the baroque? Are they in cheerful conversation or studious comparison? Because of the dialectical tension in the two studies, the finished bronzes together indicate an essential aspect of Lichtenstein’s larger body of work in bronze.

These fraternal twins, born at the same time and of the same genetic material but with different phenotypes, are studies less of personality than of decorative style. Lichtenstein returned again and again to the female head as a touchstone for his ongoing explorations of iconic motifs, from his comics-derived Pop paintings of the early 1960s to monumental self-referential sculptures of the 1990s. These works relied on the stereotypical association of women with the decorative and as vehicles for emotional expression—sensibilities deeply ingrained in the culture which Lichtenstein made starkly visible.

Roy Lichtenstein Surrealist Head, 1986

Painted and patinated bronze; 79 x 28 x 17 3/8 inches

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

His longstanding interests in deep style intensified in his bronze sculpture of the 1980s. Working through the head’s geometrical constraints, Lichtenstein used the plasticity of standardized female facial features and hair to investigate the degree to which iconic art-historical styles may be reduced to linear essentials. In this decade his sculptures efficiently composited ancient Mediterranean, Indigenous, African, and other world imagery, often in the spirit of and in response to the formal inventiveness of the modern and avant-garde sculpture of Rodin, Picasso, and Brancusi.

Though his personal style is closely associated with Pop art sourced from comic book imagery, Lichtenstein within this body of work repeatedly returned to a handful of generic images to investigate profound issues that preoccupied him, such as perception, the cognition of form, and the history of art. In the hair lies the fundamental difference between the two works, and a key to Lichtenstein’s prevailing interest in the fundamentals of period style.

-Daniel Belasco

September 5, 2022