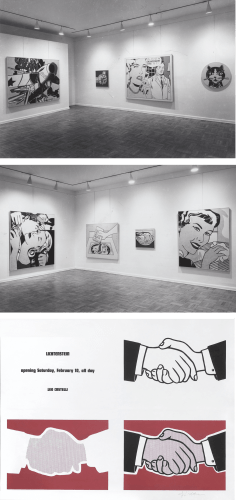

Installation views and announcement of

Roy Lichtenstein, 4 EAST 77, February 10 – March 3, 1962

For today's blog, we invited Kenneth E. Silver to write about Roy Lichtenstein's first exhibition at the gallery in 1962. Kenneth E. Silver is the Silver Professor of Art History at New York University.

Pop Art exploded into public view with a series of five solo exhibitions in the United States in 1962.[1] Counting backward, these were the Tom Wesselmann show at Richard Bellamy’s Green Gallery on West 57th Street, New York (13 November – 1 December); Claes Oldenburg at Green Gallery (24 September – 20 October); Andy Warhol at Irving Blum and Walter Hopps’ Ferus Gallery on North La Cienega Boulevard, Los Angeles (9 July – 4 August); and two exhibitions in New York that overlapped as the year began: James Rosenquist at Green Gallery (30 January – 17 February ) and Roy Lichtenstein at Leo Castelli Gallery, on East 77th Street (10 February – 3 March). Although all five exhibitions came in for a good deal of attention from the press--some good, much bad--Lichtenstein’s was the straw that broke the back of the art establishment. Life magazine ran a photo essay in 1964 that asked: “Is He is the Worst Artist in the US?”[2]

Why? What was it, I’ve asked myself, about the paintings that Lichtenstein showed at Castelli that winter—The Kiss (1961), Washing Machine (1961), Turkey (1961), The Refrigerator (1962), Blam (1962), The Grip (1962), The Engagement Ring (1961), and Laughing Cat (1961)--that made them the targets of invective for those who despised the new art movement? First of all, Lichtenstein’s source material was shockingly (demoralizingly) familiar: either war and romance comic strips and comic books, including G.I. Combat, All-American Men of War, Secret Hearts, and Girls’ Romances, for paintings like Engagement Ring and Blam; or mass-market advertising (The Refrigerator was based on a baking soda ad; the Laughing Cat image came from either a package of cat food or kitty litter).[3] For many in the art world, the low rather than high origins of Lichtenstein’s imagery wreaked havoc with the hierarchy that separated entertainment from art. Clement Greenberg, the most influential American art critic of the era, had drawn a line in the sand in his 1939 Partisan Review essay, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” when he wrote: “Where there is an avant-garde, generally we also find a rear-guard. True enough--simultaneously with the entrance of the avant-garde, a second new cultural phenomenon appeared in the industrial West: that thing to which the Germans give the wonderful name of Kitsch: popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc., etc.”[4] Pop Art, according to this analysis, was rear-guard with a vengeance.

It’s as if almost everything about the works that Roy Lichtenstein exhibited at Castelli in 1962 was calculated to enrage the likes of Greenberg. This meant, significantly, that the values of New York “action painting,” of Abstract Expressionism, were turned on their head. In place of that movement’s dedication to abstract, private, hand-made self-expression of existential seriousness, these brand-new works were figurative, public, mechanical-looking, and ironic. The fact that they mirrored contemporary life was therefore, for Greenberg and many others, a double-headed affront to avant-garde decorum: not only did they embrace commercial America, but they were representational, not abstract. In retrospect, it seems clear that by 1961 Lichtenstein was already thinking in very sophisticated ways about how art mirrors or fails to reflect the world it purports to portray (his brilliant series of “Mirror” paintings date from the early 1970s). Contrary to the notion that realist art “apes” appearances--a foundational idea that underpinned the disdain which many abstract painters and critics of the postwar era felt for contemporary mimetic art--Lichtenstein realized that all art was essentially abstract, that every mark the artist puts on paper or canvas is the stylization of a feeling, not a reproduction of reality. (The artist clearly demonstrated this in his Bull paintings, of 1973, his brilliant and funny remake of Theo Van Doesburg’s “Cow” series of 1916-17).

It was not only American commercialism that Lichtenstein’s paintings mirrored in 1962, but also its gendered codes, in which women cleaned the (suburban American) house and men fought the (Communist) enemy . . . when they were not thinking about or making love. Only four days after Lichtenstein’s exhibition opened at Castelli, the association between women and “home” was given vivid demonstration on the top rung of the social ladder when Jackie Kennedy offered her immensely successful televised tour of the newly renovated White House. Intended to appeal especially to female viewers (i.e. female voters), the tour, in which the First Lady explained to the world how she and her team of experts, headed up by Henry F. Dupont, had searched for and donated appropriate American antiques to fill the presidential residence, was broadcast by NBC and CBS, on Valentine’s Day no less. It was seen by more than eighty million viewers and syndicated globally to 50 countries, including China and the Soviet Union. On the male side of things, it is worth recalling not only that John Fitzgerald Kennedy in 1960 was the youngest man ever elected to the presidency (he was 43), but that he’d been widely hailed, with accompanying photographs, for his Second World War heroism as commander of a patrol boat, the celebrated “PT 109,” in the Pacific.

One might say that the Kennedys were acting out their assigned gender roles to perfection, closely akin to the actors in Lichtenstein’s paintings, even if no one expected a Jackie herself to baste the Thanksgiving Turkey or to drop laundry detergent into Washing Machine, or for Jack to be ejected from the cockpit of the fighter plane in Blam. But the times they were a changin’. J.F.K. and his advisors were just now gingerly getting the United States militarily involved in Vietnam, where a few years down the road fighter pilots and calamitous air strikes would give vivid, tragic meaning to Lichtenstein’s manly fantasy images. And surely the artist’s wife, Dorothy Lichtenstein, was right to say that “If he had tried to make the same paintings during the rise of feminism, I think there would have been a backlash—perhaps people would have thought that he was using women as objects.”[5] In fact, second wave feminism was just about to burst on the scene: almost exactly a year after Lichtenstein’s exhibition opened at Castelli, Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, where she railed against the idea that women could only fulfill themselves through childrearing and homemaking.[6]

It now seems obvious that the men and women, the things they were doing, and the things they were doing things with, in these iconic Pop works by Roy Lichtenstein were never intended as pictures of reality but as mirrors--true and false reflections--of contemporary life. They both celebrated democratic American vitality and critiqued vulgar homegrown commercialism; they re-inscribed traditional gender roles in the process of ridiculing them; they were meant at one and the same time as praise and parody. In their large scale, simplified forms, and brilliant color, these were works that could not be ignored—they were clean, lean, and mean. I think that Lichtenstein was in search of a New Classicism that might be confected from the muck and mire of those areas of culture most despised by the cultural elite. Like other great modern artists before and since, he wanted to extract esthetic gold from the crass visual dross of contemporary life. That he was challenging us to admire and laugh at ourselves at the same time was a very adult demand to make of his audience in 1962. Is it any wonder that not everyone liked it?

-Kenneth E. Silver

[1] Although it did not invoke the term Pop Art, the group exhibition New Realists (Sidney Janis Gallery, exhibition, 31 October – 31 December, 1962) featured most of the artists who would soon be considered Pop practitioners.

[2] “Is He the Worst Artist in the US?,” Life (31 January 1964) cited, in Robert Rosenblum, “Roy Lichtenstein: Past, Present, Future,” in exh. cat. Roy Lichtenstein (Liverpool: Tate Gallery, 1993), p. 10.

[3] Lichtenstein said the cat image was based on a “cat food package” [“Roy Lichtenstein: An Interview,” in John Coplans, ed. Roy Lichtenstein, exh. cat. (Pasadena: Pasadena Art Museum in collaboration with the Walker Art Center, 1967), p. 12]; Diane Waldman wrote that it was derived from a “bag of kitty litter,” in Diane Waldman, Roy Lichtenstein, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1993), p.4.

[4] Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review (fall 1939).

[5] Dorothy Lichtenstein and Jeff Koons (Florent Restaurant, April 11, 2008), in Lichtenstein: Girls, exh. cat. (New York: Gagosian Gallery and Yale University Press, 2008), p. 15.

[6] The Feminine Mystique was published by W.W. Norton on February, 19,1963.