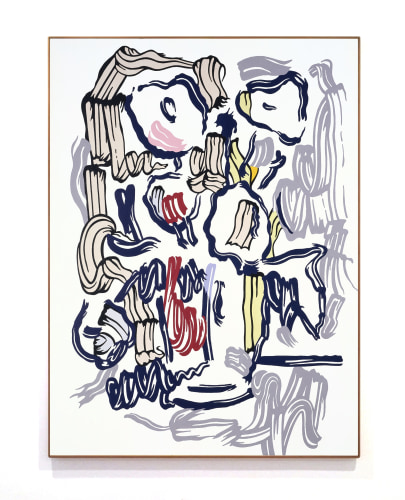

Roy Lichtenstein

Flowers in Vase, 1982

Magna on canvas

50 x 40 inches

Over the course of his career Roy Lichtenstein engaged with forms typically considered incidental to the appearance of an image, whether the Ben-Day dots used to produce cartoons, the glare reflected by mirrored or glass surfaces, or the brushstrokes that compose paintings. While as viewers we are habituated to looking past these forms to grasp the image they either help create or partially obstruct, Lichtenstein reverses this habit and directly confronts the impact these forms have on what we see. The two paintings Flower in Vase (1982) and Flowers (1982) are exemplary of Lichtenstein’s group of works which deal with the brushstroke as a form integral to the meaning of painting. What follows is a brief history of Lichtenstein’s engagement with this form from the 1960s through the 80s. Understanding this history in turn helps illuminate the guiding aesthetic and conceptual interests expressed in Flowers in Vase and Flowers.

In 1965 Roy Lichtenstein began work on his first brushstroke series. This group of paintings and prints took as their subject one the most basic units of artistic expression: the mark of the artist’s paint-ladened brush upon the canvas. In each of these works, the brushstroke appears not as the trace of a gesture, the accumulation of which produces an image, but as a deliberately created image in its own right, what the artist called a “cartoon” of a brushstroke. Rendered in unmixed primary colors and outlined in black, Lichtenstein’s stylized brushstrokes present this form as an idea: a symbol of artistic production and an object of contemplation. Lichtenstein’s interest in the brushstroke was sparked by the art historical context of the mid-sixties. Throughout the 1950s and early 60s the American art scene had been dominated by the aesthetic values of Abstract Expressionism, which glorified of the spontaneous, gestural mark—the brushstroke, the drip, the smudge—as an authentic index of the artist’s creative genius. Starting in the mid-sixties, however, a new generation of artists began to call into question these principles. Movements such as Minimalism and Conceptual Art participated in a whole-sale rejection of the Abstract Expressionist mode of art-making by abandoning painting and with it the brushstroke as the fetishized trace of the artist’s hand. Instead these movements swung in the opposite direction, producing highly intellectual works which privileged concept over form and material. Lichtenstein, however, took a more subtle and inquisitive approach in his critique of the older generation: playfully interrogating its investment in the brushstroke as the fundamental container of meaning. In this way, Lichtenstein avoided discrediting Abstract Expressionism, and indeed the entire art historical tradition out of which this movement grew, by using it as a generative premise for his own artistic practice. At the same time, by engaging with this legacy, Lichtenstein pushed back against the assumption of Minimal and Conceptual artists that painting had exhausted its innovative potential. Lichtenstein’s brushstroke paintings proved the contrary, revealing that new meaning lay in the medium’s reflexive treatment of the fundamental elements that allow it to possess and communicate meaning.

Lichtenstein continued to explore the brushstroke as both a form and an idea throughout the 1970s and 1980s, always with a conscious awareness of how past and present art movements instrumentalized this form. In his brushstroke works from the seventies, Lichtenstein further refined the idiom he had developed in the sixties: representing either a single or group of brushstrokes as static, autonomous forms against a ground of Ben-Day dots. Among the most significant examples of his brushstroke works from the seventies is the large four-sided mural he created for the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Düsseldorf in 1970.

In the 1980s Lichtenstein extended his exploration of the brushstroke-form in a new direction. Although he continued to use a clear, graphic style, he began to create paintings composed of numerous smaller strokes rather than the more sparse compositions of his earlier brushstroke series. These pieces likewise made use of a more diverse palette, including pastels shades of lavender, pink, and blue as well as earth tones such as burgundy and mustard . On the one hand, these new developments may be viewed as a response to the rise of Neo-Expressionism during the late-seventies—exemplified by the works of artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiate and Georg Baselitz—which recouped the gestural tradition of Abstract Expressionism. On the other hand, Lichtenstein’s freer treatment of the brushstroke speaks to his deepening interest in earlier forms of expressionism, including German Expressionism and Post-Impressionism. Lichtenstein’s works inspired by these art historical examples are less an effort to recreate or appropriate existing paintings, than a means of “dealing with” the creative imperatives of previous generations by channeling them through his own radical techniques of representation.

The two paintings, Flower in Vase and Flowers, both created in 1982, are representative of this later phase in Lichtenstein’s brushstroke series. In both pieces a raucous assembly of brushstroke-images appear to have been scattered at random across the canvas: there is little to distinguish the top from the bottom of the composition and the overlapping strokes seem to intentionally negate a sense of perspective. In addition, the title of these works gives them an ironic quality by encouraging viewers to look for an image of flowers, yet presenting an image of brushstrokes. Thus, Lichtenstein seems to remind us of the fact that even when looking at a naturalistic painting of flowers, we are, at a basic level, still simply looking at an aggregate of brushstrokes.

The fact that both Flowers in Vase and Flowers were inspired by the work of Paul Cézanne adds an additional layer of significance to their ironic condition. Cézanne is known for having revolutionized the medium of painting through his use thick impasto brushstrokes, which he left readily apparent in his work. This technique challenged the convention that painting ought to present an illusionistic image of reality, while elevating the means of representation to an equal level of importance as the painting’s subject. Seen in light of this influence, Flowers in Vase and Flowers may be understood as extending Cézanne’s style to its logical conclusion: in these paintings the brushstroke is no longer at an equal level of importance as the subject, but seems rather to have surpassed it.

– Renée Brown, Castelli Gallery