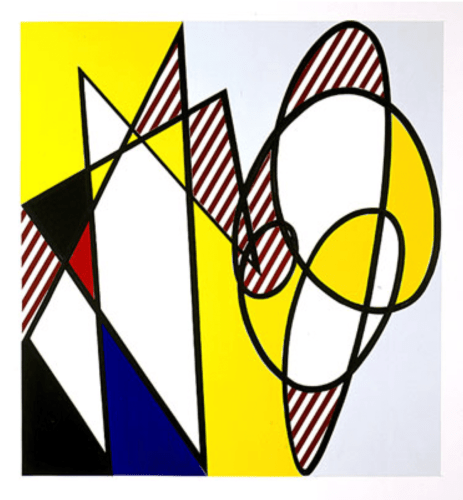

This Figure is Pursued by That Figure, 1978

Acrylic, oil, graphite on canvas

40 x 36 inches (101.6 x 91.4 centimeters)

Roy Lichtenstein was the most cerebral practitioner of Pop Art, a movement that relied on irony, that most cerebral of theatrical devices (dating back to Greek tragedy). Inspired by highly accessible source material, mostly commercial art and comic strips, his paintings camouflaged their meanings--formal and thematic, public and private--beneath an impenetrable veneer of banal representation. He made the familiar look strange and the strange familiar. One way he did this was by slowing down time: in place of the instantaneity of quick glances—reading about the daily exploits of Steve Canyon or flipping past the newspaper’s cheap, back-of-the-book, Pocono hotel advertisements—Lichtenstein offered the sustained longue durée apprehension we typically associate with galleries and museums, that is to say, with “art appreciation.” It was by making the everyday look exceptional that Lichtenstein first gained notoriety in the early 1960s—leading Life magazine to (famously) inquire, in 1964, “Is he the worst artist in America?”[i]

Coming at representation from the opposite direction, Lichtenstein just as convincingly made the esoteric look commonplace. Avant-garde abstractions in the style of Picasso, Braque, or Mondrian were reborn in his painting and sculpture as high modernist brands from which one might choose, each distinctive but readily available. This second path, the commodification of abstract art, would come to dominate his oeuvre from the 1970s until the time of his death several decades later. With these works—just as ironic as the those of the 1960s, but slyer and more sophisticated--Lichtenstein became a pioneer of postmodernism: the world-at-large was replaced by the “art world” as a point of departure. “Let’s say I just use other people’s graphic work rather than nature to do my art,”[ii] he told an interviewer in 1991.

Or other people’s sculpture, like Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne (Borghese Gallery, Rome), the reference point for Lichtenstein’s painting of 1978, This Figure is Pursued by that Figure (RLCR 2775). Here, the Baroque artist’s three-dimensional retelling in marble of Ovid’s tale from Metamorphoses is recast by Lichtenstein as a graphic two-dimensional abstraction in the primary colors, plus black-and-white, as it might have been rendered by a Cubist, or Futurist, or Constructivist in the 1920s or 30s. Or on a cocktail napkin in the 1950s (Lichtenstein was nothing if not democratic in his aesthetic sourcing). In Lichtenstein’s retelling, the Roman poet’s story of Apollo’s hot pursuit of Daphne the nymph who is saved from the god’s ravishment by her transformation into a laurel tree, sheds its mythic outline to become a modernist picture-puzzle: Apollo, lunging forward at left, is rendered as a two-part construction of angular, star-like forms and Daphne, at right, is now a yellow biomorphic squiggle with a gray shadow moving into the darkness at the right, her crown of leaves now looking like a striped beach ball. Is Lichtenstein, with a wink, equating Ovid’s literary metamorphosis of Daphne with his own magical transformation of 17th-century figuration into 20th-century abstraction?

Best Buddies (Study), 1990

Tape, cut painted paper, cut printed paper, graphite pencil on board

Board: 35 1/6 x 31 9/16 inches (89.1 x 80.2 centimeters)

Image: 30 3/8 x 27 3/4 inches (77.2 x 70.5 centimeters)

With the kind of persistent, razor-sharp logic that characterized his artistic development from beginning to end, Lichtenstein refined his visual language (and its attendant ironies) further still: by jettisoning figural reference altogether, he left himself with the rich residue of a wholly abstract gendered discourse, as in his Best Buddies (Study) (1991, RLCR 4001). Here, the men and women of Greek myth, as well as modern fighter pilots and housewives, have disappeared entirely, replaced by their visual signifiers, the purely rectilinear (male) “holding hands” with the purely curvilinear (female). Their cartoonish colors, borrowed from the Dutch De Stijl modernists, and the candy-cane stripes, are, nonetheless, recognizably Lichtensteinian—proof, one could say, that the artist was always at heart an avant-garde formalist, looking to unburden himself of subject matter which, in retrospect, might look dated.

What remained, however, was what had interested him from the very start: the pull of difference. Apart from the male-and-female social commentary of the 1960s, and beyond even “this figure” running after “that figure,” he was fascinated by the ground-zero of difference, i.e. how this-and-that are distinct categories. And, perhaps not surprisingly, it was the work of art itself, the oil-and-acrylic-on-canvas Ding an sich, that was Lichtenstein’s supreme hermeneutic device. In the late 1970s and 1980s, the artist sent-up his own obsession with impeccable craftsmanship by way of a group of minimalist geometric abstractions gone wrong. “[T]he Perfect/Imperfect paintings had to do with the shaped canvas,” Lichtenstein told Ann Hindry in 1991, “. . . in some of them, the ‘imperfect’ ones, the shapes stick out of the canvas 2 or 3 inches, as if I had made some horrible mistake.”[iii] Although he made only two works titled Perfect Painting (in 1978, no. RLCR 2751 and 1985. no. RLCR 3442), he created more than a score “with horrible mistakes,” including Imperfect Painting, 1987 [RL 1262], where the pinkish pentagon rimmed in gray exceeds the boundary of the work’s border, at left. Of course, in parodying the immaculate shaped geometric canvases of his contemporaries, artists like Frank Stella or Al Loving, he was, first and foremost laughing at himself and his own perfectionism. Who knew better than Roy Lichtenstein that the difference between a great work of art and total failure could be the matter of a few inches? As these perfectly imperfect works make clear, that little bit of difference . . . is everything.

[i] “Is He the Worst Artist in the US?,” Life (31 January 1964).

[ii] Ann Hindry, “Conversation with Roy Lichtenstein,” Artstudio [Spécial Roy Lichtenstein], (Paris, Spring, 1991; the interview took place in New York on January 7, 1991), p. 16.

[iii] Ibid.