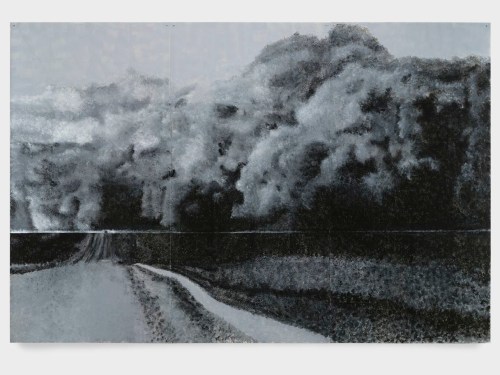

Robert Morris

1934 Mid-West Dust Storm, 2010

Epoxy on aluminum panels

96 x 144 inches

Our current exhibition, "FAR AWAY and CLOSE," presents a work by Robert Morris that was first shown in his 2011 solo exhibition at Castelli titled, 1934 and Before. On this occasion, we decided to re-post an interview between Robert Morris and MU that was first published in the exhibition catalogue.

MU And these works which you call drawings are made on…

RM Why not call them drawings?

MU Ok, Ok, call them drawings. And they are made on thin sheets of aluminum. What was the medium?

RM Mostly acrylic and some epoxy. An acrylic ground especially formulated for aluminum boat hulls was used to prepare the panels.

MU And you drew on this ground. I know that you used your hands to apply the material in your Blind Time drawings. Is that how these were made?

RM Mostly I used sponges, sea sponges, to make the works.

MU So you worked alone to make these 8 large drawings.

RM My daughter did the second dust storm drawing, which is the largest at 16' in length, and done in a sepia tone, rather than in black and white as were most of the others.

MU Can you speak about what motivated you to make works that refer to the Great Depression?

RM Well, memory has often been a focus for my work.

MU Yes, I believe this manifests itself early. The “Memory Drawings” are from ’63 aren’t they?

RM Yes, but I think memory is there in less obvious ways in most of the work.

MU But let me return to my first question about the Great Depression.

RM I was a child of the Great Depression, having been born in 1931.

MU I notice that most of the series makes reference to events of 1934. You must have very early memories.

RM No. I date most of my earliest memories to ’35. None of the images I used in the series were from my memory bank. I wanted to use memories prior to mine, so I went back a year before mine started. I suppose I was thinking about how perishable memory is, how it doesn’t survive one.

MU Except of course in recorded images or texts.

RM Exactly. And these then become public memories and exist as history. I found the images of the dust storms and some of the others in government archives.

MU What about the bread line and the strike images?

RM Also from government archives.

MU And the drawings are direct transcriptions of the photographs?

RM No, there was some alteration and manipulation of the photographic image.

MU And the image of the Nuremberg rally?

RM Based on a Riefenstahl photograph.

MU So let’s get the sources of the rest of the drawings. What about the Two Women?

RM The image of the woman with the parasol in the graveyard is based on a photograph of my mother when she was in her 20s. The other female image is based on a prehistoric so-called fertility fetish found in a cave in France and judged to be around 20,000 years old.

MU And these were literal transcriptions from photographs? The fetish image doesn’t look her age?

RM Well, I used an image of the restored object. And I altered the face of my mother.

MU Why the alteration?

RM I never liked my mother’s face, but it was not as grim as that in the drawing.

MU Why juxtapose your mother with a 20,000 year old woman, or was she the mother you always wanted?

RM I wouldn’t go that far.

MU Why the large scale? You have attacked large scale work as a form of spectacle in several of your articles?

RM It would not be the first time I have contradicted myself.

MU And why bother to transcribe the images from the photographs, why not just blow up the photographs?

RM Working at the large scale allowed me the feeling of being inside the images, of being enveloped in them, of being inside the memories and events that were prior to my existence. Isn’t the worry that we are going to miss something in the future when we are gone? But what about having missed out on Plato’s seminars or watching Donatello working?

MU But a dust storm in 1934? Sorry, but I’m skeptical of the mnemonic here. In fact it seems to me that the drawings speak to the future as much as the past. The dust storms can be read as proleptic images hinting at the coming environmental devastation. And the same claims could be made for Bread Line and Strike.

RM Well, that is 4 out of 8

MU I want to ask you about the other four, starting with Father/Engine. Did you alter the image of your father’s face as you did with that of you mother?

RM No, it is as close as I could get to the photo.

MU Why the different approaches between the two?

RM I always liked my father’s face.

MU Why juxtapose a locomotive next to it? Is this to be taken as a commentary on his character?

RM Not at all. The locomotive had to do with his working environment, which was in an industrial area next to a railroad switch yard.

MU And what about the large face in profile? It looks prehistoric, reminiscent of Neanderthal.

RM I think the image is from the 1920s. Someone’s idea of Neanderthal. But I’ve forgotten where I found the image.

MU The prehistoric female image achieves a certain resonance against that of your mother, but this bald face of vanished Neanderthal seems…

RM Well, some of the relatives on my mother’s side were rather wide and short with strong bodies and long arms.

MU Even if you think you have a few Neanderthal genes, how could that be a reason to make a bill board sized image of this long vanished creature?

RM I’ve always been impressed with how they survived for over 200,000 years.

MU Until Homo sapiens showed up?

RM Yes, until we showed up.

MU Is there some iconographic theme that ties these 8 large works together?

RM Other than that of memory?

MU As I said, I am somewhat skeptical of that claim.

RM All of the drawings, or anyway the images in them, revolve around, or provoke, a kind of fear for me, but I don’t claim this as a theme for them.

MU Well, this seems to undercut your claims for the work as somehow revolving around memory, since fear is usually directed toward present or future threats.

RM Have it your way.